Q&A: What is a heat network?

The way we heat our buildings is changing.

In Scotland, across the UK and all over the world, people are switching away from polluting gas- and oil-fired boilers in their homes and businesses. This is given urgency by the global climate emergency – burning fossil fuels for heat is only adding more carbon emissions to the atmosphere.

It's also essential to achieving Scotland’s goal of net zero by 2045.

But changing to low-carbon heating has immediate benefits, too: cleaner air, warmer homes, lower bills and more energy security.

This doesn't mean everyone will need their own heat pump, however. A heat network is a form of communal heating widely used in Europe for decades. Today, they heat the homes of more than half the population in Denmark, Sweden, Lithuania, Estonia and Slovakia.

We spoke to Kira Myers, senior carbon analyst at Edinburgh Climate Change Institute, about the basics of low-carbon heat networks in Scotland.

What is a heat network?

Kira Myers: In the most basic sense, it's pipes in the ground that move around hot or warm water.

The heat is produced somewhere else, not in your house or your premises. Rather than paying for gas that gets piped to your house, you're instead paying for heat as a service.

So, you have an energy centre that's producing your heat, which then gets piped out to buildings. The energy centre is often a very large heat pump.

What energy sources are used?

KM: It varies a lot by the type of heat network. That also hugely affects the cost. At the moment, low-carbon heat networks are often designed with electricity as the source.

The Scottish Government is skewing towards electricity as an energy source, which would mean heat pumps. The problem is that's very expensive, because electricity is very expensive.

A cheaper way to do it would be with waste heat. You get quite a few heat networks that are developing around energy-from-waste plants, which is a fancy way of saying “we burn stuff.”

Then the question is, is that really low carbon if we are burning waste to produce the heat that then goes into the heat network? But at the moment, we're burning it and not using the heat for anything. It's just being thrown out.

The Queens Quay district heating energy centre in Glasgow. This large-scale water source heat pump extracts heat from water in the River Clyde. (Image: Heat Networks Industry Council)

How do they compare to installing your own heat pump?

KM: Heat networks are more efficient than having individual heat pumps at everybody's house, because you get economies of scale by making one heat pump in one place.

It also means that if better technology comes along, you can just take that big heat pump out and replace it at source, rather than replacing it in every individual building.

Being in a heat network means you might have some equipment in your house or building. But a lot of the costs of maintaining it are paid by the energy centre and are distributed across everyone [connected to it] through a service charge, rather than you maintaining your boiler at your house.

Are there any heat networks in Scotland already?

KM: There's quite a few. You have these small-scale heat networks that are, say, one communal boiler at the bottom of a block of flats, which provide heat for everyone in the building.

Aberdeen Heat & Power is an example of quite a big network that's operating in Scotland. They generate and distribute heat to many different customers across the city.

Around Edinburgh, we have the Millerhill network. There's a new housing development called Shawfair that's going to receive heat from Millerhill, an energy-from-waste plant in Midlothian.

Where can you find information about heat networks in your area?

Google the name of your local authority and “LHEES”.

All local authorities in Scotland have to produce an LHEES, or Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategy, which includes a five-year delivery plan. One of the things that requires them to do is identify potential heat network zones.

But even then, if you're in a heat network zone, it doesn't guarantee a heat network is coming to you. It's just that you're now being considered as a potential area for heat.

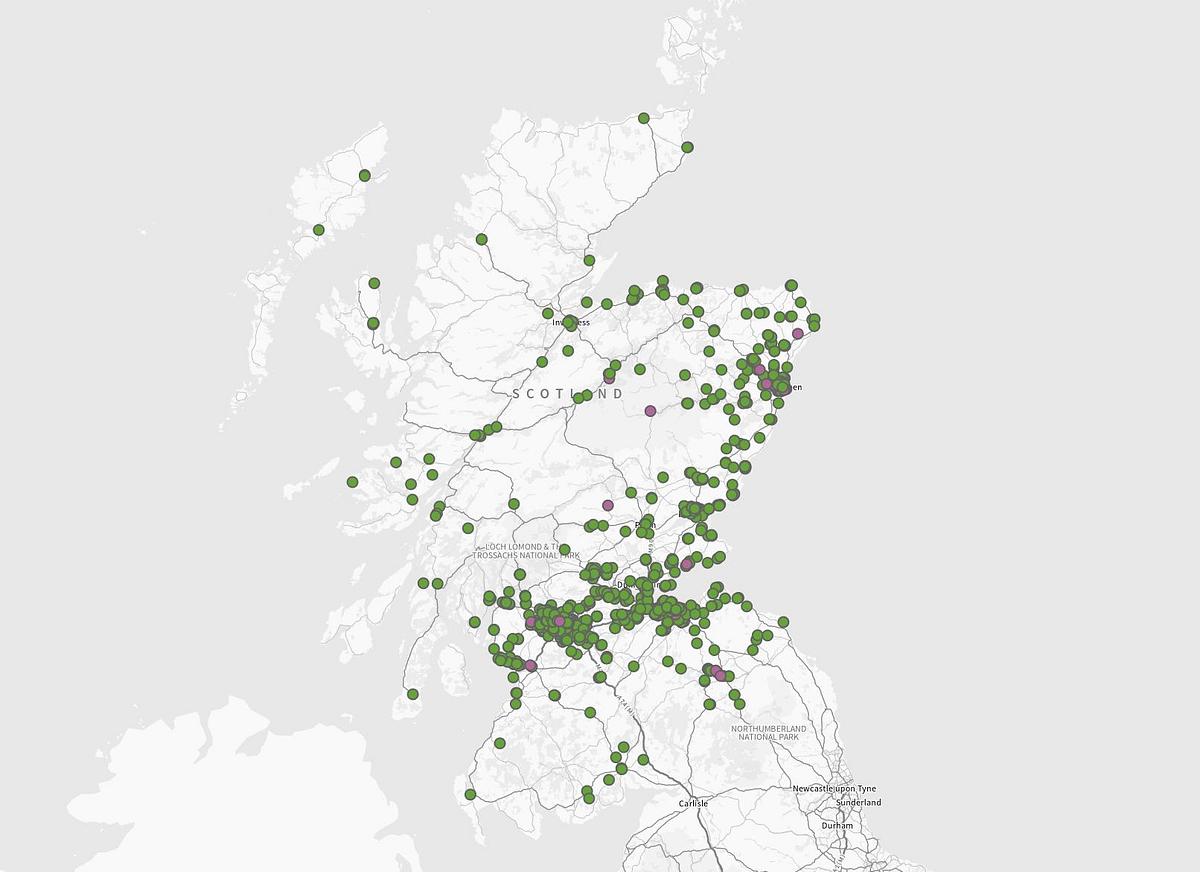

There are more than 1,200 heat networks operating in Scotland as of 2025, with 20 in development (Image: Scottish Government)

What can you do to prepare for a heat network coming to you?

Know what your energy demand is, particularly if you're a really big user.

It's possible that when local authorities go about developing these heat networks, that they will come to you and say: “We're building a heat network, how much heat do you need?” It will help to be able to answer that question and know what your peak load demand is.

Also, stay up to date. Edinburgh, for example, published their LHEES at the end of 2023. Since then, they've done a bunch of feasibility studies and consultations and are now going to publish an updated LHEES, including rejigging the zone.

We're still waiting for the Heat and Buildings Bill. A lot of things aren't going to move forward until that is in place.

Editor’s note: The Heat in Buildings Bill will set out laws for how we heat Scotland’s buildings, as well as how energy efficient the buildings need to be. This will include timescales. The Scottish government is currently revising the bill following a public consultation last year.

Once the bill passes [in the Scottish Parliament], there's likely to be some kind of expectation that once a heat network ready in your area, you either join or you decarbonise by some other means.